Melissa, who has the blog Here in the Bonny Glen and who is also the author of the wonderful The Martha Years and The Charlotte Years series (about Laura Ingalls Wilder's great-grandmother and grandmother), has a different take and some interesting questions on the decision by the California school board to remove some books from a purchase recommendation list parents and teachers had compiled:

Melissa, who has the blog Here in the Bonny Glen and who is also the author of the wonderful The Martha Years and The Charlotte Years series (about Laura Ingalls Wilder's great-grandmother and grandmother), has a different take and some interesting questions on the decision by the California school board to remove some books from a purchase recommendation list parents and teachers had compiled:(Melissa writes)and also,

In a public school district, as everywhere else, someone has to have authority over the budget. In this case, the folks who've been granted that authority are exercising their right to approve or deny the purchase of book titles on a list of possibilities. ...

...I don't dispute the rights of the folks who've been invested power over fund-dispersal to decide whether or not my books make the cut.

That doesn't prevent kids from getting hold of the books elsewhere. Can individual teachers include these titles in their classroom libraries? ...As part of a farm family with only one income-earner, I can certainly understand the financial constraints of any public school or school district.

What I'd really like to know is: What would the trustees do if parents or teachers were to donate the rejected books to the school library? If donations are regularly accepted, but these titles were refused, then perhaps it would be time to sound the censorship alarms.

What I don't understand is why common sense or at the very least these financial constraints haven't helped the trustees to distill or elaborate more clearly their policy on book selections -- guidelines they admit they need -- something along the lines of, say, "Because we have only a limited amount of funds, we will strive to purchase for our school library and our children classics new and old, and other books of literary merit."

I mentioned Charlotte Mason in my last go-around and over the weekend felt moved to look up some of Miss Mason's wisdom on the subject of children and books; two passages jumped out at me,

A child has not begun his education until he has acquired the habit of reading to himself, with interest and pleasure, books fully on a level with his intelligence. I am speaking now of his lesson-books, which are all too apt to be written in a style of insufferable twaddle, probably because they are written by persons who have never chanced to meet a child. All who know children know that they do not talk twaddle and do not like it, and prefer that which appeals to their understanding. Their lesson-books should offer matter for their reading, whether aloud or to themselves; therefore they should be written with literary power. As for the matter of these books, let us remember that children can take in ideas and principles, whether the latter be moral or mechanical, as quickly and clearly as we do ourselves (perhaps more so); but detailed processes, lists and summaries, blunt the edge of a child's delicate mind. Therefore, the selection of their first lesson-books is a matter of grave importance, because it rests with these to give children the idea that knowledge is supremely attractive and that reading is delightful. Once the habit of reading his lesson-book with delight is set up in a child, his education is––not completed, but––ensured; he will go on for himself in spite of the obstructions which school too commonly throws in his way.And, if you're still with me, CM also has this to say:

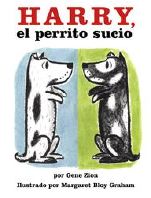

In devising a syllabus for a normal child, of whatever social class, three points must be considered:I would be the first one to agree that I would rather spend limited shopping dollars on Harry the Dirty Dog rather than on Clifford the Big Red one. And is it coincidence or just great good luck that Harry happens to be available in a bilingual edition with library binding to boot, as Harry, el perrito sucio?

(a) He requires much knowledge, for the mind needs sufficient food as much as does the body.

(b) The knowledge should be various, for sameness in mental diet does not create appetite (i.e., curiosity).

(c) Knowledge should be communicated in well-chosen language, because his attention responds naturally to what is conveyed in literary form.

Here are a few other substitutes I thought of this weekend:

Instead of the dreadful Princess School: Beauty Is a Beast, how about a real princess school, Princess Academy, the Newbery Honor book by Shannon Hale; or To Be a Princess: The Fascinating Lives of Real Princesses by Hugh Brewster and Laurie Coulter (sadly, apparently now out of print); or the pair of Robin McKinley's Beauty and the Beast retellings, Beauty: A Retelling of the Story of Beauty and the Beast and Rose Daughter; or a nice inexpensive shelf-full of the Dover reprints of Andrew Lang's "color" Fairy Books?

Instead of Disney's Christmas Storybook, might I suggest Jan Brett's Christmas Treasury? The oversize volume includes Brett's The Wild Christmas Reindeer, Trouble with Trolls, The Twelve Days of Christmas, The Mitten, The Hat, Christmas Trolls, and The Night Before Christmas.

I'm not sure of the particular "Rapunzel book" mentioned in the newspaper article, but you certainly can't go wrong with Paul O. Zelinsky's beautifully illustrated, well-told, Caldecott Medal winning version.

By the way, on a home education list this morning I found information about the Oklahoma Library Association's Sequoyah Book Awards program, established to encourage "the students of Oklahoma to read books of literary quality." Might be something for the folks in California to consider.

Another aside here, because this has been niggling at me for the past few days, from the newspaper article again: "Of the Potter, Artemis Fowl and 'princess' books, [a parent] said, 'The fifth-graders, that's all they're into. They can't afford $30 books. They will lose interest in reading and lose interest in academics.' "

You know, one can get good books quite cheaply (psst... new at Bookcloseouts, new and used at Amazon, Powells, and abebooks.com, and even at one's local secondhand book shop). And one can, and should, interest kids in quality writing from an early age, so that one doesn't have to fall back on the argument that if they can't read the likes of Princess School or Artemis Fowl, they'll lose interest in reading, which almost sounds like a threat to me. Reminds me very much of the "chicken nugget" theory of kids' food, which Jennifer Steinhauer wrote about the other month in the New York Times Sunday Magazine; she cited some chefs' rules at home for making sure their kids "not only eat better [but are] better eaters":

4. Eschew Baggies filled with Goldfish. (Car rides are exempt). "If kids are hungry, they're going to eat," [one chef] said. "If you fill them up on [Moral of the story? Raise your kids on the good stuff and teach them the value of quality, whether it's food or books and whether you're a family or a school. It doesn't cost any more and is better for you in the long run.Disney books] Bugles, they won't."

5. Buy them the most expensive chocolate you can afford. Who craves Ho Hos when they've had Scharffen Berger? I do. But I wasn't raised on the good stuff.

I have to go lie down now. And read my kids a good book. And eat some dark chocolate (which I may or may not share with them).

No comments:

Post a Comment